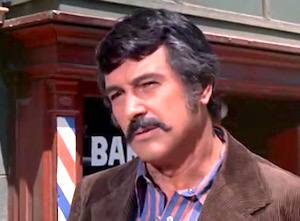

McMillan and Wife

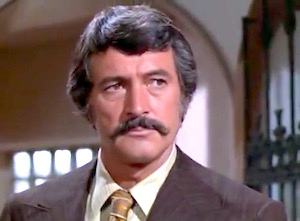

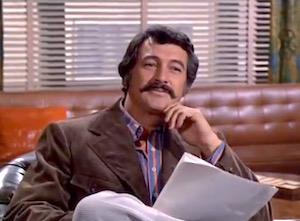

McMillan & Wife was a lighthearted American police procedural starring Rock Hudson and Susan Saint James in the title roles that ran on NBC from September of 1971, to April of 1977.

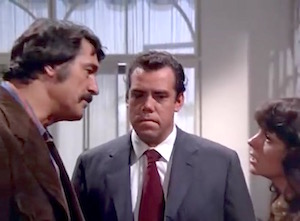

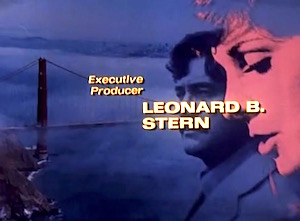

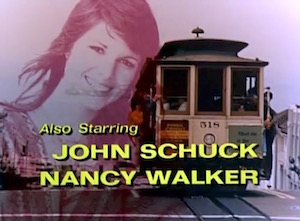

McMillan & Wife were Stuart McMillan (Rock Hudson) a 40-something San Francisco police commissioner, and his attractive, bright and good-natured 20-something wife Sally (Susan Saint James). Often, Mac and Sally attended fashionable parties and charity benefits before their sleuthing. John Schuck and Nancy Walker helped round out the cast, as, respectively, Sgt. Charles Enright, who was Stuart's earnest if often ineffectual assistant, and Mildred, the McMillans' sarcastic, hard-drinking maid. Because of the show's emphasis on the McMillans' May-September romance, as well as its light-of-heart storytelling style, critics sometimes said that it brought the screwball sleuthing of The Thin Man into the 1970s. The show was created by Leonard B. Stern, who already had an impressive writing and producing pedigree, including work on such shows as The Honeymooners, The Phil Silvers Show, and Get Smart.

See the McMillan and Wife Show Intro

The series ran as McMillan & Wife for five seasons and as McMillan for a sixth season, for a total of 40 shows. Like the other two original serials in the NBC Mystery Movie, McMillan & Wife was an immediate hit.

Due to a contract dispute between Susan Saint James and the studio, Sally McMillan was killed off in an airplane crash during the fifth season. With one of the main characters missing, the show was retooled and retitled McMillan. Nancy Walker and John Schuck also left the series, each to pursue greater stardom in their own shows. Martha Raye joined the cast as Mildred's sister Agatha, who served colorfully as Mac's new housekeeper in his new house, while Richard Gilliland joined as Mac's new police liaison Sergeant DiMaggio.

The series pilot, Once Upon a Dead Man, was an uncertain venture for creator Stern, who wasn’t at all sure how the executives at the three existing TV networks would receive it. In fact, the strong possibility that Once Upon a Dead Man would end up being a one-off may have been one of its attractions for Hudson, who wasn't attracted to small-screen productions. But once NBC showed an interest in the series and asked Hudson to rethink his resistance to it, he came around. And that was all that was needed to make it a Go for the network. “Once Rock was involved,” recalled Paul Mason, an early producer and writer of the show, McMillan & Wife “got the highest priority” and was soon tagged as the third spoke in the NBC Mystery Movie wheel.

Before casting the show's “& Wife”, Stern “talked to many gifted actresses”, including such luminaries as Jill Clayburgh and Diane Keaton. But a lunchtime meeting in Los Angeles between Stern, Hudson, and the convivial Susan Saint James — a brunette in her mid twenties who'd memorably played sultry pilferer Charlene “Charlie” Brown in It Takes a Thief — ultimately won Saint James her place in the new series. “Rock felt comfortable with Susan,” Stern remembered, “so we said, OK, we’ll go with her. And she turned out to be an ideal choice, ’cause she had an innate sense of mischief. And that’s what the role calls for.”

The two lead roles as conceived by Stern had great potential for romantic and comic chemistry. Stewart “Mac” McMillan was a middle-aged U.S. Navy veteran with a background in CIA intel and a string of ex-girlfriends. He'd been a prominent defense attorney before being tapped to serve as San Francisco's police commissioner. Sally McMillan, (née Hull), was the free-spirited daughter of Fred Hull — “a great criminologist” — and had clearly inherited her father's investigatory gene. “She grew up in the business,” Mac would observe early on. “She knows a clue when she meets one.”

In a stroke of great luck, Hudson's and Saint James's on-screen romance gave McMillan & Wife a touch of real magic. Although Hudson was a closeted gay (as was sadly customary at the time), he came across on the show as an understanding and supportive older husband, while Saint James was smart, kindhearted, and tremendously appealing. (The series’ regular bedroom scenes, in which Saint James dressed in a long, red, No. 18 football jersey, fueled many a teenaged boy's fantasies.) The pair seemed to be very much in love, and to relish each others' company.

According to film expert Richard Meyers, “McMillan and Wife were as much George Burns and Gracie Allen as they were Nick and Nora Charles, because Police Commissioner Stewart McMillan’s wife, Sally, was as wacky as Gracie and as prone to finding corpses as Nora.” Meyers especially admired Saint James: “It is not that easy to be kooky without being cloying or completely unbelievable, but Saint James pulled it off. In every episode, it seemed, Sally would uncover a body or something and spend the rest of the show getting kidnapped, attacked, threatened, or else all three ...”

The McMillan & Wife plots often focused on friends, family, or social acquaintances of the commissioner and his wife, often someone from Mac’s espionage days, or an afflicted concert pianist colleague of Sally’s, or the commissioner’s still-feuding Scottish relatives. In one episode, a small Bay Area temblor topples part of the McMillans’ chimney to reveal a cadaver bricked up inside. Another focused on Sergeant Charles Enright (John Schuck) — the loyal but somewhat slow-witted cop serving as Mac’s official assistant — who'd seemingly murdered his jealous ex-wife. Yet another episode found housekeeper Mildred (Nancy Walker) attacked in her hotel while she served on a sequestered trial jury.

Some of the McMillan and Wife plots were outrageous. In season two's “Terror Times Two”, for example, Mac is abducted by mobsters and replaced by a surgically altered double — a career criminal who on the one hand has no qualms about offing a hospitalized informant, but on the other draws the line at jumping in the sack with unsuspecting Sally. (The plot device of a McMillan impostor was used again the next season in “Cross and Double Cross,” in which Mac switched places with a mirror-image baddie to snag a shipment of stolen gold.)

But then complete authenticity was never the ultimate aim of McMillan & Wife. Robert Daley, a one-time New York City deputy police commissioner turned novelist, pointed this out in a New York Times article. Writing of an episode in which Mac gave chase on foot after a suspect fleeing aboard one of San Francisco’s iconic cable cars, Daley observed:

Police commissioners do not catch suspects with their bare hands, any more than presidents of General Motors build cars with their bare hands, and for exactly the same reasons. There is too much other work to do — administrative work — which is perhaps not as much fun as catching crooks, but which is absolutely essential if the machine is to work at all.

And how many people know what Police Commissioners actually do? One thing they don't do is inhabit the police world accompanied by their spouses... Especially if said spouse is as luscious as Mrs. McMillan. No police work would get done while she was around, and eventually her presence would become an intolerable investigative hindrance.

McMillan himself admitted that his job description didn’t include heroics or derring-do. The issue came up in an exchange with his fictional San Francisco police chief, Andrew Yeakel (Jack Albertson), in Once Upon a Dead Man:

McMillan: “Andy, is it necessary for you to keep me under constant surveillance?”

Yeakel: “You’re the commissioner. We don’t want anything to happen to you.”

McMillan (laughing): “Nothing ever happens to commissioners.”

Despite this conceptual fancy, or maybe because of it (what audience is there, after all, for a realistic, bureaucratic depiction of a police commissioner's work, even if the commissioner looked like Rock Hudson?), McMillan & Wife turned into a hit for NBC. It also brought more public attention to beautiful San Francisco, which at the time was also the setting for Ironside and The Streets of San Francisco. While it's true that much of the Mystery Movie series was shot on the Universal back lot, the actual city was prominent in the show. Watching McMillan & Wife today on DVD, it’s fascinating to see how the Bay Area has changed since the 1970s, especially thanks to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, which providentially (if violently) brought down the waterfront’s Embarcadero Freeway, an eyesore that made many guest appearances over the show’s run.

The interior set of the McMillans' home in the pilot episode, by the way, was actually Rock Hudson's house. In the second episode they moved to a new home, with exterior shots done on Greenwich Street in San Francisco. The address for the couple was once given in the show as 250 Carson Street. In later episodes a different house served for exterior shots. In the final season McMillan, newly widowed, moved into an apartment, and the house was never seen or mentioned again.

After its fifth (1975-1976) year, McMillan & Wife suffered dramatic changes. A contract dispute led to Susan Saint James's exit from the series and John Schuck and Nancy Walker pursued other projects. NBC, loathe to lose its moneymaker, soldiered on without them. To fill its plenitude of plot holes, the writers had commissioner McMillan take up residence in a new apartment, acquire a new but suitably eccentric housekeeper — Mildred’s sister, Agatha (Martha Raye) — and assigned to him another police aide, Sergeant Philip DiMaggio (Richard Gilliland). The show was appropriately retitled McMillan, and it limped along for half a dozen more installments, but Saint James’ absence was sorely felt, and the parade of less-interesting girlfriends into widower Mac’s life seemed only to highlight all the more harshly Sally's absence. In 1977, McMillan was finally cancelled, as was the NBC Mystery Movie wheel itself (though the studio kept Columbo going for another year).

Rock Hudson went on from his lackluster year alone on McMillan to star in the 1979 TV mini-series The Martian Chronicles (based on Ray Bradbury’s 1950 sci-fi classic), and he was featured in 1980's The Mirror Crack'd, adapted from Agatha Christie’s 1962 novel. He would later land a recurring role on the prime-time soap Dynasty, but his health and physical condition were deteriorating and would soon grow dire.

After years of heavy drinking and smoking, Hudson suffered a heart attack late in 1981. An emergency quintuple heart bypass surgery took him out of action for a year and led to the cancellation of his new TV series, The Devlin Connection. Though he recovered from the heart surgery, Hudson continued to smoke. His ill health continued while filming The Ambassador in Israel, with Robert Mitchum, during the winter of 1983-84. Things continued on a downward course through the rest of 1984, prompting different rumors that Hudson was suffering from, among other ailments, liver cancer. His face and physique became cadaverous.

In June of 1984, Hudson was diagnosed with HIV, but he fought to keep it a secret and to keep his career alive. A year later he accepted his fate and announced to the world that he was dying of AIDS. The news was a sensation in the media and elsewhere, and had an historic effect on public awareness and attitudes about what had, until then, been an obscure disease. It would never be that again. Rock Hudson — born Roy Harold Scherer Jr. — died on October 2, 1985. He was 59.