Infamous

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother 40 whacks

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father 41

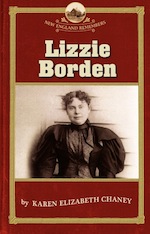

The name of Lizzie Borden will forever be linked to a pair of gruesome and sensational axe murders that were committed on August 4, 1892 in Fall River, Massachusetts. On that day, Lizzie Borden's father, Andrew Jackson Borden, and her stepmother, Abby Borden, were brutally hacked to death by an unknown assailant whose identity remains a mystery down to the present day, more than 120 years later. The murders remain hotly debated among experts and aficionados on both sides of the question as it relates to the guilt or innocence of Lizzie Borden. After a jury acquitted her of the crimes, the commonwealth of Massachusetts has never seen fit to charge anyone else.

The Borden house.

Family Background

Lizzie Borden's father, despite coming from a wealthy family in the area, grew up in exceedingly modest surroundings and was not financially successful as a young man. This changed as he grew older – he found success by building and selling furniture and caskets. Later he prospered as a property developer and as the director of several local textile mills. At the time of his death his assets included a substantial amount of commercial property – he was also the director of the Durfee Safe Deposit and Trust Company and president of the Union Savings Bank.

In spite of this, Andrew Borden was conspicuously frugal. The Borden home, for example, had no indoor plumbing on the ground and first floors. It was also built near Borden's businesses, in distinct contrast to the practice of most of Fall River's economic elite, who preferred living in their own distant and fashionable enclaves.

Upbringing

Lizzie and her older sister Emma had a religious upbringing; both attended Central Congregational Church. As a young woman Lizzie was involved in many church-related activities – she taught Sunday school to children of recent immigrants to America, served as treasurer for the Christian Endeavor Society, and and was involved in the Women's Christian Temperance Union.

Family Tensions

The Bordens' live-in maid Bridget Sullivan testified at the inquest that Lizzie and Emma rarely had meals with their parents. Furthermore, Lizzie revealed that she called her stepmother "Mrs. Borden" instead of "Mother" and would not say whether she and her stepmother were cordial with each other.

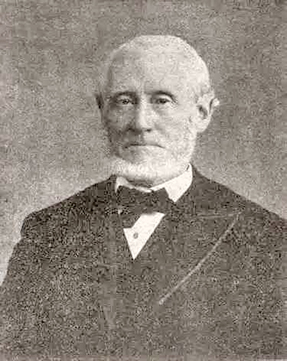

Andrew Borden.

Abby Borden.

Emma Borden.

Lizzie Borden.

Bridget Sullivan.

In May 1892, an incident took place where Andrew, believing that pigeons belonging to Lizzie were attracting intruders, killed them in the family barn using a hatchet. Two months later a family argument erupted that led both sisters to take prolonged "vacations".

Financial tensions flourished in the family in the months leading up to the murders. Andrew's gifts to various branches of the family lay at the center of many of them. When Abby's relatives received a house, Lizzie and Emma demanded and received a rental property – which they sold back to their father later for cash.

Just before the murders, a brother of Andrew's first wife paid a visit to discuss the transfer of another property. On the night before the murders, John Vinnicum Morse, the brother of Lizzie's and Emma's deceased mother, visited the home to speak with Andrew regarding certain business matters.

In addition to this, the entire household had been violently ill for several days. The family doctor said it was food left on the stove for use in meals over several days, but Abby suspected poisoning – Andrew Borden was not a popular man.

Maggie, Come Quick! Father's Dead...

On August 4, 1892, an unusually hot day, Andrew Borden had breakfast with his wife and made his customary rounds of the bank and post office, returning home about 10:45 AM. Bridget Sullivan testified that she was in her third-floor room, resting after cleaning windows. Just before 11:10 AM she said she heard Lizzie call out to her from downstairs, "Maggie, come quick! Father's dead. Somebody came in and killed him." ("Maggie" was the name of an earlier maid that family members sometimes used when calling for Sullivan.)

Andrew Borden's body.

Abby Borden's body.

Andrew was collapsed on a couch in the downstairs sitting room, struck 10 or 11 times with a hatchet-like weapon. One of his eyeballs had been split cleanly in two, as if he were asleep when attacked. While neighbors and doctors comforted Lizzie, Sullivan soon discovered Abby Borden upstairs in the guest bedroom. Her skull had been crushed by 19 blows.

Investigating police soon found a hatchet in the basement. Though free of blood, it was missing most of its handle. Lizzie was arrested a week later, on August 11. On November 7 a grand jury began hearing evidence. They indicted Lizzie on December 2.

Trial

The following June Lizzie's trial began in New Bedford. Among the key issues addressed were the following:

The hatchet head in the basement was not definitively shown to be the murder weapon. The prosecution claimed that the killer had removed the handle because it was bloody; one officer testified that a hatchet handle was indeed found near the hatchet head, but another officer contradicted him.

Although no bloody clothing was found, a few days after the murder Lizzie had burned a dress in the stove. She claimed it had been ruined when she brushed up against some fresh paint.

Amazingly, a similar axe murder had occurred nearby, shortly before the Borden trial. The defendant in that crime was shown to have been out of the country at the time of the Borden murders, however.

Evidence was excluded from the trial showing that Lizzie had tried to purchase prussic acid (supposedly for cleaning a sealskin cloak, according to the defendant) from a druggist the day before the murders.

Because of the mysterious illness that had afflicted the Borden household before the murders, the family's milk and Andrew and Abby's stomachs (removed during autopsies conducted in the family dining room), were tested for poison;none was found.

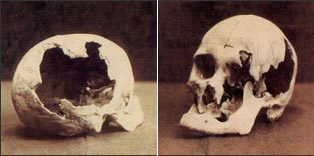

The victims' heads were removed during autopsy. After the skulls were used as evidence in the trial – Borden fainted when she saw them – they were later interred at the foot of each grave.

The skulls of

Andrew and Abby Borden.

Verdict and Precedent

On June 20, after deliberating for just an hour and a half, the jury voted for acquittal.

The Lizzie Borden case served as a kind of precursor to such sensational later trials as that of Bruno Hauptmann, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, and O.J. Simpson in the annals of American legal proceedings.

The Borden Murders continue to be the object of speculation. Various authors have proposed the following candidates as the real murderer:

Ironically, Lizzie herself, in spite of her acquittal – at least one writer has proposed that she killed while she was in a fugue state.

Bridget Sullivan, enraged, perhaps, because she had been ordered to clean windows on a hot day – while still not fully recovered from the mysterious illness that had struck the household.

One William Borden (Andrew Borden's illegitimate son) – supposedly after failing to extort money from his father.

Emma Borden, having established an alibi at Fairhaven, Massachusetts (about 15 miles from Fall River) is alleged by some to have secretly returned to Fall River to commit the murders, then returned again to Fairhaven in time to receive the telegram informing her of them.

Later Life

After their trial the Borden sisters moved to a much larger, more modern house in the fashionable "Hill" neighborhood of Fall River. From then on, Lizzie began to use the name Lizbeth A. Borden. At their new house, which Lizbeth named "Maplecroft," the sisters were able to hire a staff that included live-in maids, a housekeeper and a coachman.

Lizbeth continued to be ostracized by society. Her name again came into the public eye, in 1897, when she was accused of shoplifting.

After the removal of her gallbladder in what proved to be the last year of her life, Lizbeth was chronically ill. She died of pneumonia on June 1, 1927 in Fall River. Funeral details were confidential and attendance was sparse. A little more than a week later, Emma died from chronic nephritis at the age of 76. The sisters never married. They were buried side by side in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery.

Lizzy and Emma Borden's graves.