The Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping

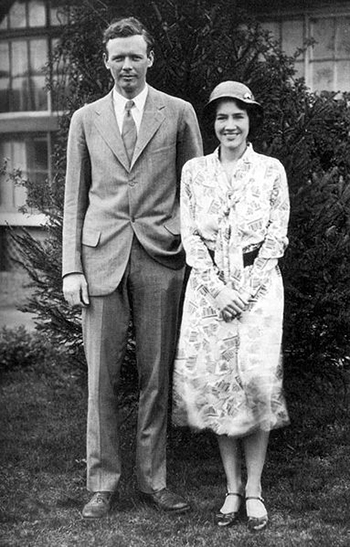

Top: Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. Bottom: Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

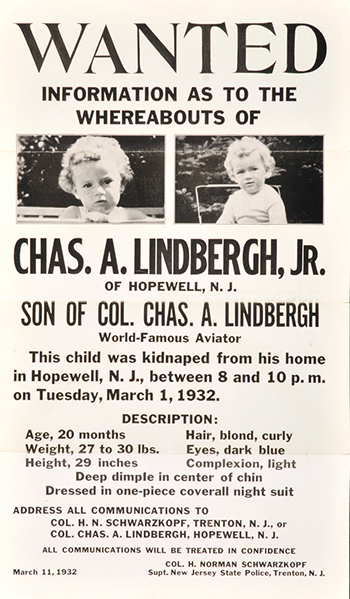

The kidnapping of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the son of world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was one of the most sensational and highly publicized crimes of the 20th century. The two-year-old was taken from his family home in East Amwell, New Jersey on March 1, 1932. Over two months later, on May 12, 1932, his body was found in Hopewell Township, just a few miles away from the Lindbergh home, dead from a massive skull fracture.After a two-year investigation, police arrested Bruno Richard Hauptmann and charged him with the crime. Hauptmann was tried and found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. Still proclaiming his innocence, he was executed on the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison on April 3, 1936.

Because of this crime, Congress passed the Federal Kidnapping Act, commonly known as the "Lindbergh Law". It made transporting a kidnapping victim across state lines a federal crime.

Abduction

At 8:00 PM on March 1932 1st on a cold rainy night, Betty Gow, the Lindbergh family nurse, put 20-month-old Charles Lindbergh Jr., to bed in his crib. Returning two hours later to check on him, she found the crib empty. She checked to see if the baby was with his mother (who had just emerged from a bath), then came down to tell Mr. Lindbergh, who was in the library directly beneath the baby's room. Alarmed, Charles Lindbergh went immediately upstairs to search for his son, who was indeed gone. In the course of his search he found an envelope on the window sill above the radiator.

The Lindbergh house.

Lindbergh called police, then took his gun and checked around the house in search of intruders. Twenty minutes later the police arrived with the media in tow, as well as the Lindbergh family lawyer. As the night progressed, police discovered a suspicious tire print in the mud near the house. Widening their search, they discovered three pieces of a crudely-constructed ladder in a nearby bush.

Investigation

After midnight, a fingerprint expert arrived at the home and examined the note left on the window sill as well as the ladder. Despite the 400 partial fingerprints and some footprints he found on the ladder, nothing was of any investigative value. Nor could he find a single usable fingerprint in the baby's room. The presence of smudges did indicate, however, that the nursery had not been wiped clean.

The ladder used by the abductors.

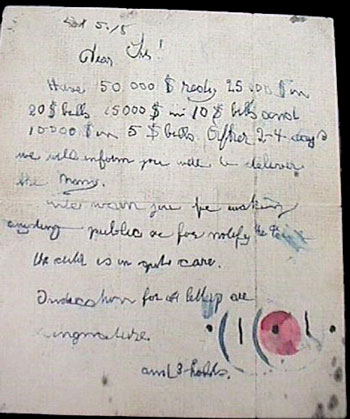

Solid evidence outside the house was equally hard to come by. Police inspected the ransom note found by Lindbergh. The handwritten letter, riddled with spelling and grammatical mistakes, read as follows:

The ransom note:

Dear Sir!

Have 50.000$ redy 25 000$ in

20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and

10000$ in 5$ bills After 2-4 days

we will inform you were to deliver

the mony.

We warn you for making

anyding public or for notify the Police

The child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are

Singnature (Symbol to right)

and three hohls.

There were two overlapping circles below the message, with holes punched through the red circle and outside the overlapping circles on either side.Dear Sir!

Have 50.000$ redy 25 000$ in

20$ bills 15000$ in 10$ bills and

10000$ in 5$ bills After 2-4 days

we will inform you were to deliver

the mony.

We warn you for making

anyding public or for notify the Police

The child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are

Singnature (Symbol to right)

and three hohls.

The morning after the kidnapping, President Herbert Hoover was informed. Though the case did not present any obvious grounds for federal action (kidnapping was then considered a local crime), Hoover announced that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child. The Bureau of Investigation (later to become the FBI) was authorized to investigate. Officials in New Jersey offered a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little Lindy". The Lindberghs put up $50,000.

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter, postmarked in Brooklyn and determined by authorities to be genuine, came via the mail to the Lindberghs.

A second and then a third ransom letter, also postmarked in Brooklyn, followed shortly. The third letter warned that since the police were now involved, the ransom had been raised to $70,000.

Enter John Condon

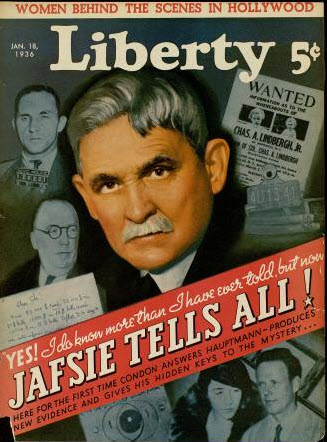

John F. Condon – aka "Jafsie".

A prominent man named John F. Condon – known as Jafsie (derived phonetically from his initials, "JFC") – came forward to insert himself into unfolding events. In a letter to the Bronx Home News, he offered $1,000 to the kidnappers if they would turn the baby over to a Catholic priest. The kidnappers wrote back, agreeing to accept Condon as their intermediary with the Lindbergh family.Condon, acting in accordance with the kidnapper's instructions, placed a classified ad in the New York American: "Money is Ready. Jafsie". He then awaited further instructions.

Eventually a late-night meeting between "Jafsie" and a supposed member of the kidnapping group took place at Woodlawn Cemetery. Condon told investigators the man sounded foreign, but because he stayed in the shadows during the encounter he could give no physical description. The man claimed his name was John, and said he was a Scandinavian sailor and part of a gang of three men and two women. The Lindbergh child was being held on a boat, and was supposedly unharmed, but the gang was not yet ready to return him without a ransom payment. When Condon expressed skepticism over whether "John" actually had the baby, John promised to give him proof. He then asked Condon a chilling question: "... would I burn [be put to death], if the package [baby] were dead?"

On March 16, 1932, a package was mailed to John Condon. It contained a toddler's sleeping suit, and another ransom note. Condon showed the clothes to Lindbergh, who identified them as his son's. Condon took out a new ad in the Home News: "Money is ready. No cops. No secret service. I come alone, like last time."

On April 1, 1932, Condon opened a new letter from the kidnappers. They were prepared to take payment.

Ransom

The ransom was packaged in a custom-made wooden box, in hopes that it could be identified later. The ransom money consisted of gold certificates that were soon to be withdrawn from circulation. Anyone passing large amounts of them would draw attention to themselves and help authorities identify the kidnappers. Although the bills were not marked, their serial numbers were recorded by the Bureau of Internal Revenue Intelligence. On April 2, Condon was handed a note by an anonymous cab driver. At another late-night meeting with "John", Condon told him that they had been able to raise only $50,000. "John" took the money and gave Condon a note, which said the baby was in the care of two women who, supposedly, were innocent bystanders.A Terrible Discovery

On May 12, 1932, delivery driver William Allen pulled his truck to the side of the road in Hopewell Township -- roughly 4.5 miles south of the Lindbergh home. Walking to a grove of trees to relieve himself, he discovered the body of a toddler. Allen notified police.

The body of the Lindbergh baby, found on May 12, 1932.

At a morgue in Trenton, New Jersey, the badly-decomposed body was autopsied. The skull had been fractured. The body appeared to have been chewed on and attacked by wildlife. There were indications that someone had tried to hastily bury it.Lindbergh and Gow identified the baby as little Charles Jr., based on the overlapping toes of the right foot and the fact that it was clothed in a shirt that Gow had made. The child had presumably been killed by a blow to the head. Mr. Lindbergh was insistent on having the body cremated afterward.

When Congress learned of the child's death, legislation was passed into law that made kidnapping a federal crime.

Violet Sharp.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect an inside job committed by someone in the Lindbergh inner circle. Suspicion fell on Violet Sharp, a servant. She'd given inconsistent testimony about her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping – had appeared nervous and suspicious during questioning. Before investigators could develop their case against her she committed suicide by ingesting silver polish containing potassium cyanide. Only after her death was her alibi confirmed. Police learned that the threat of losing her job had driven her to taking her own life.

A New Suspect

Despite the fact that Charles Lindbergh stood by him, John Condon was also investigated. His home was searched, but nothing was found.His conduct grew increasingly flamboyant. While riding a city bus, he supposedly saw a suspect and announced his secret identity to all present, ordering the bus to stop. The surprised driver obliged, and Condon sprang from the bus after the stranger, but lost him in the crowd.

Condon's actions were widely criticized. At one point he appeared in a vaudeville-style reconstruction of the kidnapping. Under the title "Jafsie Tells All," Liberty Magazine printed a multi-part account of Condon's involvement in the Lindbergh kidnapping.

Tracking the Ransom Money

The investigation began to languish. With few developments and little evidence to go on, police focused on the ransom payments. A pamphlet was published in New York City with the serial numbers of the ransom bills. Some of them turned up in scattered locations, some as far west as Chicago and Minneapolis, but the people spending them were elusive.At Last, A Suspect

For more than two years, FBI Agent Thomas Sisk and New York Police Detective James Finn worked the Lindbergh case. They laboriously tracked down many bills from the ransom money as they were being spent in New York City. A map compiled by Finn tagged each find and a pattern emerged: many of the bills were being passed along the Lexington Avenue subway, which connected the East Bronx with the German-Austrian neighborhood of Yorkville on the east side of Manhattan.On September 18, 1934, a gold certificate from the ransom money came to the attention of Finn and Sisk. It had been noticed by a teller of the Corn Exchange Bank at 125th Street and Park Avenue in Manhattan. A New York license plate number, 4U-13-41-N.Y, was written in the margin of the certificate by a gas station manager, Walter Lyle, who made the notation after receiving it from a customer he thought was acting suspiciously and might have been a counterfeiter.

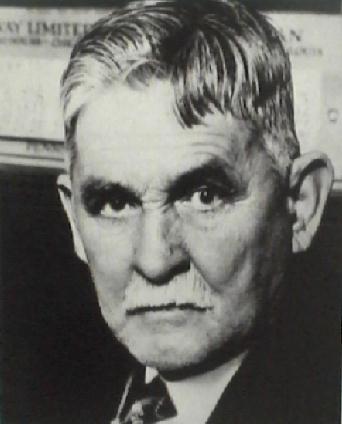

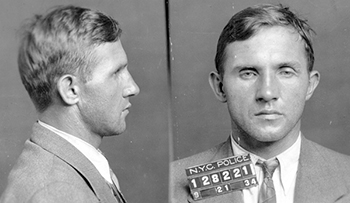

Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Municipal records tied the number to a blue Dodge sedan owned by one Richard Hauptmann of 1279 East 222nd Street, in the Bronx. Hauptmann was a German immigrant with a criminal record in his homeland.When police arrested him, Hauptmann had a twenty dollar gold certificate on his person. A search of his garage turned up $14,000 of the ransom money.

During his interrogation, Hauptmann insisted that the money had been left with him by Isidor Fisch, a friend and one-time business associate. Fisch had died shortly after returning to Germany. According to Hauptmann, it was only after Fisch's death that he, Hauptmann, had discovered the shoe box and its contents. He took the money for himself because it was supposedly owed him from a business deal he and Fisch had made. Hauptmann repeatedly denied any connection to the crime or knowledge that the gold certificates were in fact ransom money.

But in a search of his apartment by police, incriminating evidence that placed him at the heart of the crime was discovered:

| • | A notebook containing a sketch for the construction of a ladder similar to that found at the Lindbergh home. |

| • | John Condon's telephone number and address, written on a closet wall. |

| • | A piece of wood, which was determined by an expert to be a perfect match to the wood used in the ladder found at the crime scene. |

The Trial

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder – to which he pled not guilty. He was held at the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, New Jersey, and the trial quickly became a sensation: reporters swarmed the town; every available hotel room was booked.Edward J. Reilly was hired by the Daily Mirror to serve as Hauptmann's attorney, in exchange for the rights to publish Hauptmann's story in their newspaper. New Jersey Attorney General David T. Wilentz led the prosecution.

In addition to Hauptmann's possession of over $14,000 in ransom money, the State brought in eight handwriting experts to point out for the jury the many similarities between words and letters in the ransom notes and in Hauptmann's writing specimens. Only one expert was called by the defense in rebuttal.

Photographic evidence based on the forensic work of Arthur Koehler for the Forest Products Laboratory was introduced by the State. It showed that wood from the ladder at the crime scene was similar to a plank taken from the floor of Hauptmann's attic – the kind of wood, the direction of tree growth, the factory milling pattern, the inside and outside surfaces of the wood, and the grain on both sides were all identical. Two curiously-placed nail holes also lined up with a joist splice in Hauptmann's attic.

Asked by prosecutors about the presence of John Condon's telephone number in his closet, Hauptmann could only say, "I can't give you any explanation about the telephone number."

Lindbergh on the witness stand.

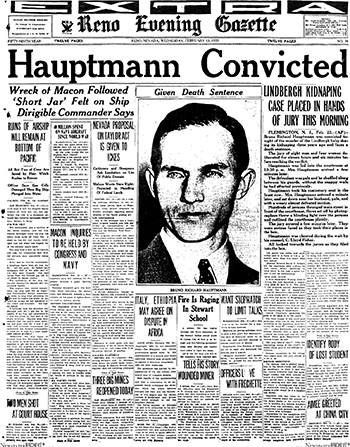

The damning evidence piled up: Condon and Lindbergh both testified on the stand that Hauptmann was the "John" they had met in Woodlawn Cemetery. Another witness, Amandus Hochmuth, claimed to have seen Hauptmann near the scene of the crime.Hauptmann was convicted – and the jury sentenced him to death. He turned down a substantial offer from a Hearst newspaper for a confession, and rejected a last-minute deal that would have commuted his execution to life in prison in exchange for a confession.

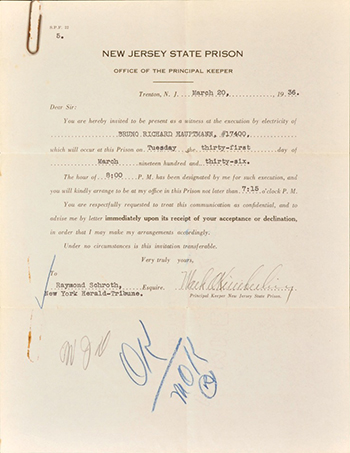

Hauptmann died by electrocution on April 3, 1936, just over four years after the kidnapping.

Hauptmann's conviction made headlines.

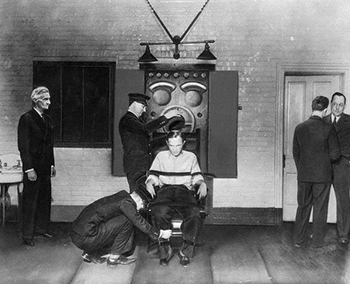

Invitation to the execution of Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Staged re-enactment of Hauptmann's execution.

Controversies and Lingering Questions

A handful of reporters and investigators raised questions about the case after Hauptmann's death. Accusations of witness tampering and evidence planting arose, but nothing came of them. Almost fifty years later, Anna Hauptmann sued the state of New Jersey twice over its execution of her husband. The suits were dismissed.Like other notorious crimes, the Lindbergh kidnapping has been the subject of hoaxes and alternative theories.

Erastus Mead Hudson – a fingerprint expert familiar with the then-rare silver nitrate process of fingerprint collection off of wood and other surfaces resistant to print gathering by previous means – discovered that Hauptmann's fingerprints were not present on the wood, even where the man who built the ladder would have had to touch it. When he reported this to police, an officer told him, "Good God, don't tell us that, Doctor!" The ladder was then washed of all fingerprints, and Hudson's findings were suppressed.

Several books have been written declaring Hauptmann's innocence. Typically they raise the following issues:

| • | Sloppy police-work, leading to contamination of the crime scene. |

| • | An investigation compromised by interference from Lindbergh and his associates. |

| • | Incompetent legal representation of Bruno Hauptmann. |

| • | Unreliable witnesses and evidence presented at trial. |

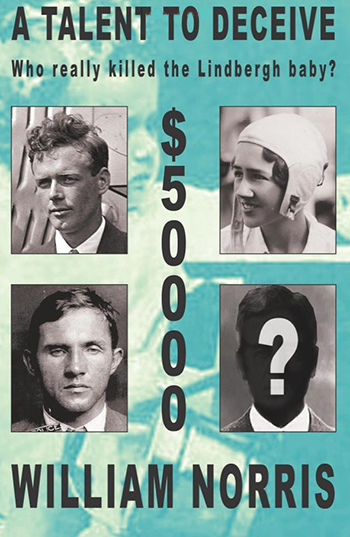

British investigative writer William Norris, in his book A Talent to Deceive, does more than declare Hauptmann's innocent – he accuses Lindbergh himself of a cover-up of the killer's real identity. Though it offers no proof, the book accuses Lindbergh's brother-in-law, Dwight Morrow, Jr., of the crime.

At least one contemporary writer takes issue with these theories. Jim Fisher, a professor at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania and a former FBI agent, has authored two books on the subject: The Lindbergh Case (1987) and The Ghosts of Hopewell (1999). In opposing what he considers to be a "revision movement" that swirls around the Lindbergh case, he discusses at length the pros and cons of the evidence presented at trial, summarizing his conclusions this way: "Today, the Lindbergh phenomena is a giant hoax perpetrated by people who are taking advantage of an uninformed and cynical public. Notwithstanding all of the books, TV programs, and legal suits, Hauptmann is as guilty today as he was in 1932 when he kidnapped and killed the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lindbergh."

The truTV program Forensic Files re-examined the physical evidence from the kidnapping in 2005, using today's more advanced scientific techniques, and concluded that the ladder found at the crime scene had been made from wood taken from Hauptmann's attic. Forensic document examiners, each working independently, came to the conclusion that it was "highly probable" that the kidnapper's notes had been written by Hauptmann.