Summary

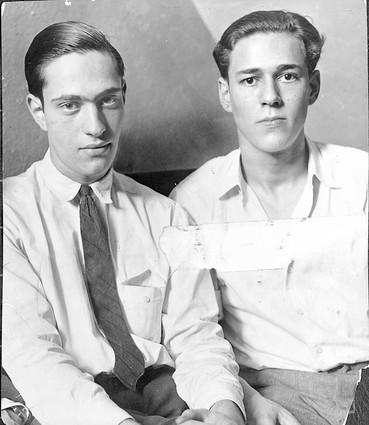

Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were wealthy University of Chicago law students who kidnapped and murdered 14-year-old Robert "Bobby" Franks in 1924, in Chicago. They were motivated by their desire to commit a "perfect" crime.

After their capture by police, Leopold and Loeb retained Clarence Darrow as their defense counsel. Darrow's advocacy in their trial was enormously influential in the capital punishment debate, becoming a touchstone for supporters of the concept of prison as rehabilitation instead of punishment. Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life imprisonment. Loeb was knifed to death by a prison inmate in 1936; Leopold was paroled in 1958, eventually dying from a diabetes-related heart attack at the age of 66 in 1971.

Background

Nathan Leopold was born on November 19, 1904 in Chicago, the son of wealthy German Jewish immigrants. A child prodigy who spoke his first words at the age of four months, he had an IQ measured at 210. At the time of the murder he was a University of Chicago undergraduate and attending law school. In addition to being an accomplished ornithologist, he claimed to be fluent in 27 languages.

Richard Loeb was born on June 11, 1905 in Chicago, to the family of Albert H. Loeb, a wealthy Jewish lawyer and vice president of Sears. Like Leopold, Loeb was intellectually gifted, skipping several grades in school, though he lacked Leopold's academic rigor.

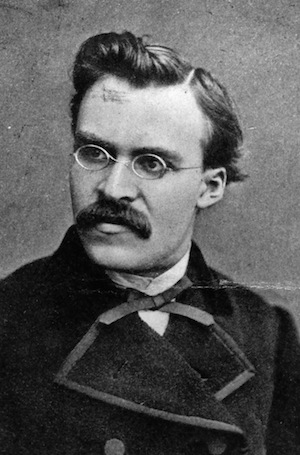

The pair knew each other casually while growing up, but did not become close friends until meeting at the University of Chicago as teenagers, where they quickly formed a strong alliance, spurred in part by their mutual interest in crime. Leopold also had an interest in Friedrich Nietzsche's theory of the superman.

German philosopher Friedrich

Nietzsche, originator of the

theory of the "Superman".

It was not long before the duo moved beyond thinking about and discussing crime to committing it themselves. Leopold became an accomplice to Loeb, who was the dominant partner of the two. Starting with petty theft and vandalism, they broke into a fraternity house at the university and stole penknives, a camera and a typewriter. These minor transgressions whetted their appetite for larger ones. Soon they graduated to more serious crimes, such as arson.

Disappointed when none of their criminal exploits made it into the papers, Leopold and Loeb then made a fateful decision. Inspired by the Nietschzean theory of "Supermen" – superior beings who were unaccountable to society's laws and moral prohibitions because of their greater intelligence and abilities – they began plotting a crime of much greater seriousness. When they finally acted on it, the infamy they craved would be theirs.

"A superman ... is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do."

– Nathan Leopold, in a letter to Richard Loeb

The Perfect Crime

Over the course of seven months, Leopold and Loeb worked out the details of their "perfect crime". They would kidnap, assault, and murder a young boy. They would pick him out randomly. Though neither of them lacked for personal wealth, they would send the boy's family a ransom letter.

They took pains to account for every step and stage of the crime – from the choice of murder weapon, to body disposal, to the wording of the ransom note, to how best to obtain the ransom money undetected, to how to minimize and conceal physical evidence.

Under the name of 'Morten D. Ballad', Leopold rented the car into which their victim would be lured and then killed. The murder weapon was purchased – a chisel. On Wednesday, May 21, 1924, the time had come for the aspiring killers to put their plan in motion. Leopold was 19 at the time. Loeb was 18.

They drove around the Harvard School For Boys in the Kenwood Area of Chicago, searching for a young boy. In court Leopold would later admit to using his bird viewing binoculars. Purely by chance, they found their target: Robert "Bobby" Franks, the son of Chicago millionaire Jacob Franks. Loeb actually knew him; Bobby was both a neighbor and a cousin of Loeb's, who had played tennis at the Loeb residence many times.

Robert "Bobby" Franks,

with his father.

They pulled up alongside Franks, 14, and offered him a ride. Initially, Franks balked. Loeb persisted and eventually convinced Bobby to ride with them, supposedly to discuss a tennis racket he used. Franks relented and climbed into the front passenger seat. With the unsuspecting boy under their control, Loeb drove and Leopold sat in back, armed with the chisel.

Loeb struck Franks several times in the back of the head with the chisel before dragging him into the back seat of the car and gagging him with a rag. Franks lost consciousness soon afterwards. The young killers pulled the car over and Loeb moved from the back to the passenger seat. They moved Franks's body to the back seat and covered it.

Acting in accordance with their plan they headed for their dumping spot near Wolf Lake in Hammond, Indiana – an area Leopold was familiar with from his many bird-watching excursions. As evening came they had dinner at a small sandwich place. After their meal, they waited for night fall, and when it was dark enough proceeded to dump their victim's body. Leopold and Loeb stripped Franks's corpse of its clothes, leaving them by the side of the road. They poured hydrochloric acid on the boy's genitals, and on an abdominal scar to make post-mortem identification more difficult. They hid the body in a culvert by the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks near 118th Street, just north of Wolf Lake.

Word Spreads

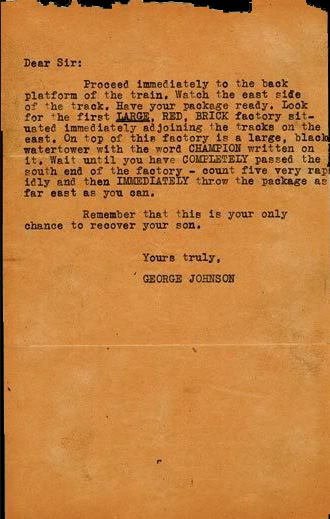

By the time they returned to Chicago, word had spread of Franks's disappearance. Leopold called the boy's mother and, using the name "George Johnson" told her that her son had been kidnapped. They would later use the same name when they typed the ransom note on their stolen typewriter. They burned their blood-spotted clothing, tried to clean the blood-stained upholstery on the rented car, disposed of the typewriter… then played cards for the rest of the evening.

The ransom note.

The ransom note reached the Franks family the next morning. Hours later Leopold and Loeb phoned the Frankses again and instructed them to go to a local drug store and await further instructions. Then the plan began to unravel; the Frankses forgot to write down the address of the drug store and were unable to communicate further with the killers. Then a Polish immigrant found Bobby's body and reported it to police.

Police at the crime scene.

Law enforcement investigations were now underway throughout Chicago. Rewards were offered to the public. Leopold went about his daily routines as inconspicuously as possible, but Loeb foolishly inserted himself into the police investigation, going so far as to offer theories to anyone who would listen. Incredibly, he told witnesses at one point, "If I were to murder anybody, it would be such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks."

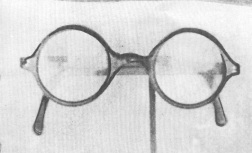

While searching for evidence, police found a pair of eyeglasses near the crime scene. Though the prescription and frame were common, the glasses came with an unusual hinge. Only three people in the city of Chicago had purchased such glasses. One of them happened to be Nathan Leopold. To add to their woes, the destroyed typewriter was also discovered. Police quickly zeroed in on Leopold and Loeb, taking them into custody.

Nathan Leopold's eyeglasses.

Confessions

Loeb confessed first, outlining the crime in copious detail to investigators. He stressed how brilliantly the murder had been planned... and he blamed it all on Leopold. Loeb claimed it was Leopold who'd sat in the back of the car and struck Bobby Franks with the chisel, while he, Loeb, had driven the car.

Meanwhile, police interrogators had Leopold in an adjoining room. In his version of events it was Loeb who had killed Bobby. Although their confessions were generally consistent on most of the facts in the case, each blamed the other for the actual killing. During the trial, a witness named Carl Ulvigh testified that the driver of the kidnap car had been Leopold.

Why?

As the scions of wealthy families, Leopold and Loeb had not killed for money. Instead they had been motivated by the sheer thrill of taking a life, and their expressed desire to commit the "perfect crime" as a way of ratifying for themselves their sense of moral superiority. Leopold's evocation of Nietzsche's Superman theory as a philosophical justification further fascinated, baffled, and angered the public. Theirs was an exotic kind of depravity.

Clarence Darrow

The trial of Leopold and Loeb became one of the first media spectacles of the 20th century. Fearful that their child might be sentenced to death, Loeb's family hired the renowned defense attorney Clarence Darrow – a passionate opponent of capital punishment – to defend the boys against capital charges of kidnapping and murder.

Clarence Darrow.

In a surprising move that ran counter to public and media expectations, Darrow had his clients plead guilty and so spare themselves a jury trial. It was a shrewd strategy. The defendants' wealth and the circumstances of their crime could well have led to a guilty verdict and a one-way trip to the gallows. Instead, the case would go before Cook County Circuit Court Judge John R. Caverly, whom Darrow believed to be sympathetic to a bid for life imprisonment.

Dueling Experts

Both Darrow and the prosecution brought in some of the county's most notable psychologists. The prosecution's experts testified that the boys, though unusual, were quite sane. Darrow's experts claimed the opposite. Still smarting from Judge Caverly's dismissal of a jury trial, prosecutor Robert Crowe called more than a hundred witnesses to the stand, in hopes of proving to the judge that Leopold and Loeb were homosexual perverts (the two were in fact lovers as well as friends). In tune with the cultural norms of the time, the pair's sexual relationship was spoken of in whispers, with the courtroom cleared of women and reporters. Rumors nonetheless spread that Franks had been sexually assaulted – but the coroner found no evidence to support them.

Darrow's Speech

On the final day of the trial, Darrow gave an impassioned speech that was as much a jeremiad against the moral horrors of war – the great slaughters of World War I were still fresh in the minds of many – as a defense of his young clients.

"For four long years the civilized world was engaged in killing men," Darrow cried before the Judge. "Christian against Christian, barbarian uniting with Christians to kill Christians; anything to kill. It was taught in every school, aye in the Sunday schools. The little children played at war. The toddling children on the street. Do you suppose this world has ever been the same since? How long, your Honor, will it take for the world to get back the humane emotions that were slowly growing before the war? How long will it take the calloused hearts of men before the scars of hatred and cruelty shall be removed?"

To the consternation of the prosecution and much of the pubic, Judge Caverly agreed, sentencing Leopold and Loeb to life plus 99 years in prison. The aristocratic young murderers had escaped the death penalty. But their troubles were far from over.

Prison

Leopold and Loeb began their sentences at Joliet Prison. Although official prison policy was to keep them apart as much as possible, they conspired to preserve their relationship. Leopold was eventually transferred to Stateville Penitentiary – as was Loeb sometime later. Once reunited, they taught classes in the prison school.

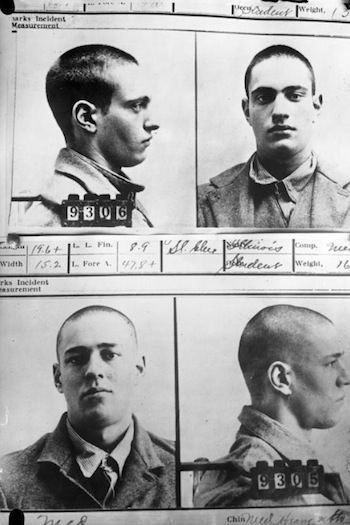

Leopold and Loeb's mug shots.

Leopold in Stateville prison, 1931.

For a while, their families gave them generous financial support in prison. Word of this – and publicity going back to the crime itself – left their fellow prisoners with the permanent impression that the two were rich snobs, and ripe for ongoing shakedowns. The duo suffered as a result.

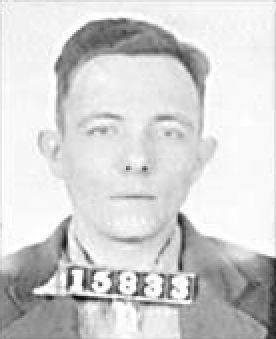

James E. Day.

Early in 1936, Loeb was attacked by fellow prisoner and one-time cell mate James E. Day with a straight razor in a shower room. Though he was taken straight to the hospital doctors could not save him. Leopold consequently fell into a deep depression.

Leopold Alone

Over time, Leopold recovered psychologically from the loss of Loeb. He busied himself by organizing the prison library, set up a better schooling system, taught students, wrote an autobiography, and worked in the prison hospital. In 1944, he took part in the Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study, subjecting himself to voluntary malaria infection so that researchers could test medicines and cures on him.

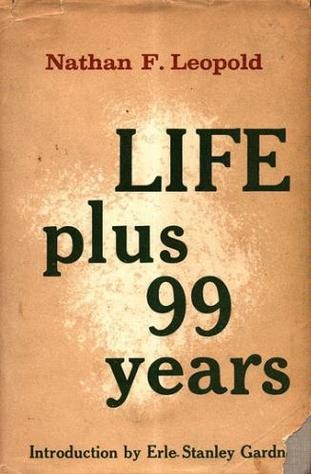

In 1954 his autobiography, 'Life + 99 Years', was finally published.

After 33 years in prison, Leopold was paroled in 1958. He moved to Puerto Rico to escape media attention and married a widowed florist. Time and trial left their mark on him. The arrogant young man who had once embraced the murderous philosophy of Nietzsche now spoke of his appreciation to the Church of the Brethren for its willingness to accept him as a medical technician at its hospital in Puerto Rico.

Neighbors and co-workers at Castañer General Hospital in Adjuntas knew him simply as "Nate". He worked as a lab and x-ray assistant. He was also active in the Natural History Society, traveling throughout Puerto Rico to study its bird life. In 1963 he compiled and published the Checklist of Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Leopold died of a diabetes-related heart attack on August 29, 1971, at the age of 66.

Cultural Impact

Leopold and Loeb have inspired many works in fiction, theatre, and film, including the 1929 play Rope by Patrick Hamilton, which was revived on BBC television in 1939 and served as the model for Alfred Hitchcock's film of the same name in 1948, which starred Jimmy Stewart. Fictionalized versions of the Leopold and Loeb's crime are featured in Meyer Levin's 1956 novel Compulsion and its 1959 film adaptation. John Logan's 1988 play Never the Sinner was based on contemporaneous newspaper accounts and highlighted the killers' homosexuality.